LISTENING TO WALLS

Sarah Swords

Working across radio, film and TV, Sarah is a freelance writer, director and photographer. Her work explores the inextinguishable capacity of the human spirit from a black heavyweight boxing champ fighting apartheid in 1950’s South Africa to cowboy poets fighting to save their beloved land from corporate mining invasion. Always in search of a story her favourite phrase is ‘Carpe Diem’.

Façade: the ‘face’ of a building from ‘faccia’ It or ‘facia’ Latin.

Just as the saying ‘walls have ears’ has been used for centuries across the globe as a warning against glib or unkind talk, so the human face and parts of the body have been connected to buildings and the natural world.

© Sarah Swords 2019

In Japan, ‘walls have ears and sliding doors are eyes.’ In Wales there are ‘eyes in the hedges and ears in the banks’. In Croatia ‘Forests have ears and fields have eyes.’ The Biennale Foundation in Pune, India has just announced a ‘Speaking Walls’ project. Eyes are ‘the windows to the soul’; there is the ‘hip roof’, ‘a rib vault’, and a ‘footprint’. Human traffic around a building is known as ‘circulation’.

I am fascinated by the notion that old walls and buildings have long been thought to be the battery storage of their history, soaking their pasts into their very fabric - sounds from past marriages, dances, parties, events; happiness, laughter, music, dancing, anger, shouting… in other words past lives. An experiment conducted in Dorchester Assizes pushed microphones into the wattle and daub walls and recorded the sounds of voices emanating from within.

What buildings have seen and heard could tell us so much… if only we would take the time to listen.

I live in an old cider pub with my husband Peter. The pub is no longer working although we try our best to keep the spirit alive a few times a year in our small, very thirsty community. It had a skittle alley in the garden, long since derelict; it had fallen into disrepair when the pub started going downhill twenty-five years ago.

Last year it was decided that something needed to be done before winter snowfall took the roof down completely. So we cashed in a pension and began the process of breathing life back into the old gal. Why she is female I don’t really know, but she is. I am sitting inside her now like Jonah in his whale surrounded by books and a lifetime’s paraphernalia. A year ago it was a different story.

The decay was prolific; it was a miracle that she was still standing. Covered in ivy, swallows nesting in her rotting eves and gaping three-inch cracks at the gable end, the alley was literally falling down the hill towards the next village.

© Sarah Swords 2019

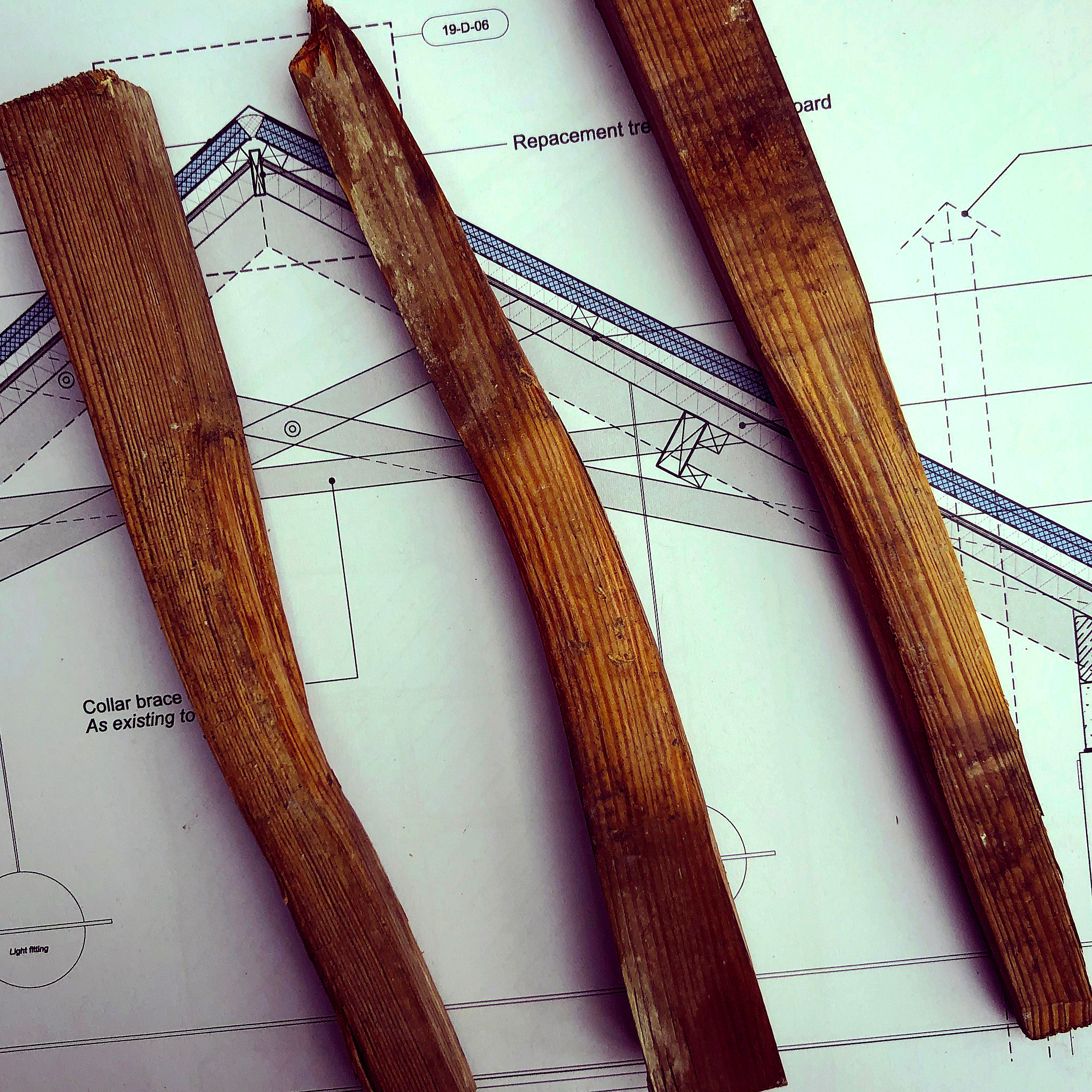

Work began in June 2018 by stitching her together and taking off the roof. She looked desperately vulnerable, but scaffolding meant we could get up close to the timbers and stones that had been laid over one hundred and fifty years ago. Stone lintels jutted out to support enormous oak beams whose hand saw marks were the same today as when they were made, handmade pegs supported the huge scissor truss spanning the roof.

A window upstairs was supported by three cast iron bars that came from the firebox grate of a Somerset coalfield steam engine - (upcycling at its best!) A swallow’s nest was tucked into a corner in what had been the village’s Pigeon Club Headquarters. A crumbling Wills cigarette scoreboard stood against the cobwebbed wall; beer mats, towels, glasses, ashtrays and a price list lay on a massive pile of bird droppings, next to it an old suitcase spewed rotting 60’s dresses and old family photographs. A bonneted baby smiled out from a titanic perambulator surrounded by faded roses in a forgotten garden.

In this place people had celebrated marriages, births and deaths – a young lad was laid out in the alley after a fatal mining accident. Men (and latterly women) had played skittles against other villages long before any notion of the middle classes coming to the country and buying their way into a bucolic idyll. The hamlet was a tiny farming and mining community with a butcher, a baker - no candlestick maker that I can find, but a pub and a skittle alley that was their meeting place. A place of entertainment, of letting go, of gossip and, without doubt, the occasional drama – when, in 1870, miners asked for (and were refused), a wage increase of half a penny the mine manager was shot in an enraged scuffle. He survived, the mine did not.

© Sarah Swords 2019

Both of us felt a great responsibly not only to the men and women in the village who knew and loved the alley but to those who came before them. We wanted to use the building as a studio and workspace but it was vital to preserve its look, atmosphere and integrity. In order to achieve this we would re-use, recycle and allow the building to dictate what she wanted.

Our architect - Lee Holcombe of Studio Four Point Ten - was extremely sensitive to this brief and incorporated as much of the original building as he could. The large Crittal windows were all kept, the original concrete floor including the markers for skittles, kept. A magnificent cobbled floor was unearthed at one end of the building. This had been a cow shed at one time and is now the kitchen area. Two rare scissor trusses are the crowning glory in the roof, their wooden pegs carved by young apprentices in the late 1800’s, still smooth and beautiful.

Over the years we have been given a multitude of discarded treasures from guttering and downpipes, parquet flooring (now the stairs and a seat), windows, bricks and a stove (swapped for some roof tiles). Local auctions, reclamation sites (radiators from Glastonbury, water butts and bricks from Frome, doors from Wells), flea markets and eBay have provided everything we have needed to design and style a spectacular space that feels as if it has always been there.

“What buildings have seen and heard could tell us so much… if only we would take the time to listen.”

At the end of the alley we built a lean-to glasshouse out of all that we had left over from the build. On the side a pergola from the original timbers which were too weak to use but too good to burn. How much good timber is burnt everyday on building sites? But that’s another story…

As I sit here, a year after starting this project, I can truly say this is a place of peace, a place of creativity – a bit of a sanctuary. She informed us of what was needed and how far to go. It’s a happy place; I believe it always has been.

We listened to the walls, I hope they like what they see.